Reflecting on ten years of practice: the challenges of digital security training for human rights defenders

Digital security and privacy have become central concerns for NGOs and activists worldwide, who increasingly rely on digital technologies in their work on sensitive issues. While a significant amount of resources, effort and energy have gone into building the capacity of civil society in digital security and privacy over the past decade, questions regarding the impact of these efforts, the challenges continuously faced, and the difficulty of long term change have not been given the attention they deserve. Following a decade of work training human rights defenders and activists in digital security, Tactical Tech recently undertook a process of applied research, learning and reflection over the course of 18 months in order to more clearly find paths forward and to share our learnings with a broader community invested in strengthening civil society.

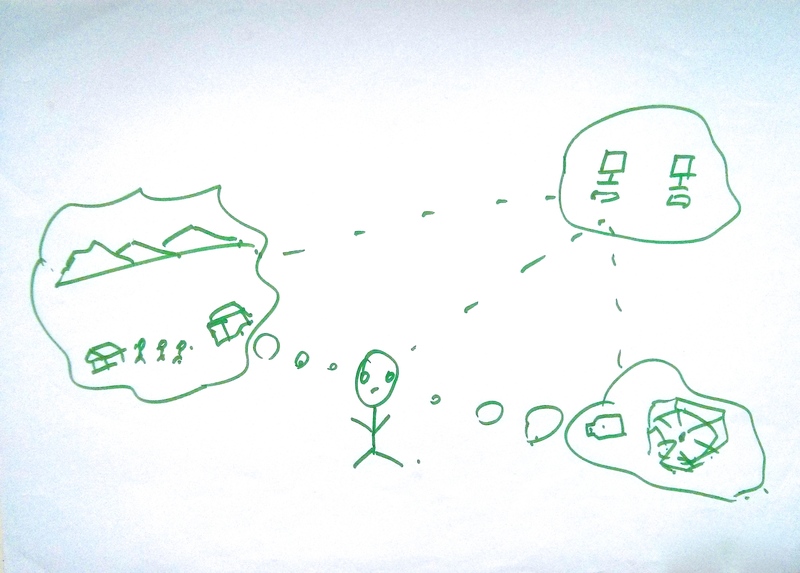

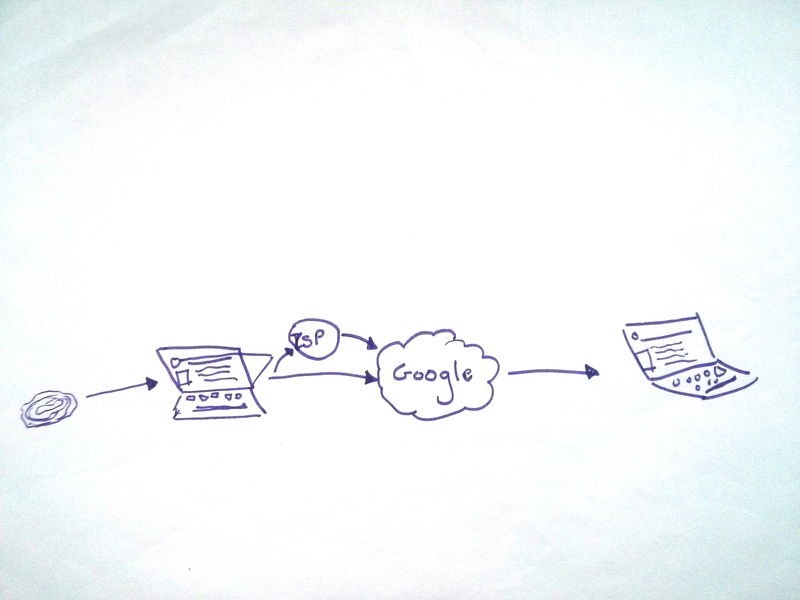

This image and the others used on this site were created as part of a training exercise during the Security in Context study. Participants, who were human rights defenders and advocates, were asked to draw how they perceived the internet.

Background

Tactical Tech began providing advice and training on digital security to human rights defenders internationally in 2005. This work steadily increased in scope and scale over a period of nearly ten years. By 2013, when the applied research projects outlined here were conceived and designed, we had an extensive digital security capacity building programme and were training an average of 1500 human rights defenders per year. Through our practice we had developed, tested and iterated a learning methodology and curricula with an informal and growing network of trainers. We had shared this with over 100 others through our training-of-trainer events and had built-up the most heavily utilised online independent non-profit digital security resource worldwide, Security in-a-box, along with our partner Front Line Defenders.

In addition to direct training, we developed a methodology for awareness-raising on digital security and privacy known as 'flash training', and the demand for capacity building was so significant that we were turning away approximately 40% of requests for support due to limited resources and capacity. We had reached a natural peak in our work building the digital security capacity of human rights defenders, independent journalists and activists worldwide, yet demand continued to rise.

While the feedback from our trainings was extremely positive and the ever increasing demand from NGOs, activists, funders and international organisations came entirely through word of mouth recommendations, we were increasingly dissatisfied with the uptake of the digital security techniques after trainings. Part of this was symptomatic of a clash between the usability of the tools and strategies available, and the severity of the risks faced. Yet part of this was also due to a need to rethink our approach given the mounting nature of the challenge. Although we had continuously iterated and improved our curricula to the point that it was widely shared and used by other trainers in the sector - and was extremely well received by participants - we felt that there was a gap between the results we wanted to see and the outcomes we were able to achieve. For this reason, during what we perceived to be a natural peak in our work, we did not want to go forward without reflecting more deeply on the challenges faced by groups we sought to support, on our methodology, and on the overall design of our capacity building intervention. It was this that led us to establish the 'Security in Context' applied research and learning project.

Shifting Landscapes

During the decade in which we established our place in the field of digital security, the environment in which we worked also changed significantly. These changes could be witnessed not only in the challenges faced by NGOs and activists, and their increasing need for support, but also in the increasing number of organisations and individuals who wanted to provide digital security training and advice within the NGO sector, and the amount of funding available for such work. Tactical Tech also shifted its role during this time. Still providing direct training to human rights defenders and activists, yet increasingly playing a role in developing the sector overall: convening meetings of trainers, technologists and practitioners, sharing our methodology and curricula with others and training trainers at the local and international level. During this time, we observed challenges in the expanding field, a lack of common understanding of what good training practices were, disparate skill-levels and approaches of trainers, and differences between expectations and the planned outcomes of trainings, at times leading to mismatches between the skill sets and goals of trainers and funders and the needs of those being trained. The set of questions that arose from these observations led us to design a second complementary research project, one that focused on the challenges, needs and observations of the trainers who were trying to meet this demand - a set of reflections that we hoped could help strengthen and develop this informal community in the future.

For Tactical Tech, it took a somewhat brave leap of faith to question and test our established work so openly. However, we could see that not only were the digital security challenges and threats faced by human rights defenders and activists worldwide not subsiding, but they were actively growing. We faced a strategic dilemma about how best to scale our work and better meet the needs of our communities, with a long term view to having greater impact and creating more systemic change. For this reason, we felt it was essential to undertake this effort to examine more deeply what we thought we knew intuitively and had learned from experience; something that would give us a solid base before moving forward with developing and iterating new models for capacity building.

This image and the others used on this site were created as part of a training exercise during the Security in Context study. Participants, who were human rights defenders and advocates, were asked to draw how they perceived the internet.

The Research

Tactical Tech was in a strong position to embark upon this research due to the relatively unique depth and breadth of our experience in the field, however working as practitioners to undertake two in-depth research and reflection based initiatives required the support of the communities we worked with, as well as our partners and funders. With their collaboration, we embarked on a learning, evaluation and applied research process, planned not only to help Tactical Tech better serve its communities, but also to facilitate understanding and reflection within the broader community invested in supporting the digital security capacity building of NGOs and activists worldwide.

The resulting applied research and learning initiatives centred on two focused yet complementary questions which we hoped would unpack a deeper and broader set of assumptions and open up new lines of enquiry for future reflection and learning. These were simply expressed as, 'How well are the needs of human rights defenders met through digital security capacity building efforts?' and 'What makes a good trainer?'.

The research focusing on human rights defenders allowed us to 'take the temperature' of the current environment and the experiences of those trying to learn about and incorporate digital security into their work. It was not a comprehensive study, but rather a snapshot of the predicaments, tensions and difficulties of these processes and an indication of potential breakthroughs and barriers. The study indicates the socio-technical nature of the challenges people face and therefore the necessity to think about capacity building within a contextual framework. It shows that participants are less preoccupied with technological processes per se and more with strategies, choices and their interdependencies, recognising digital security as both a trade-off and a process.

Training environments present an important place for exchanging and developing these strategies and, as currently designed, serve to successfully shift participants in the direction of some changes in their practices. Yet there is still a significant struggle in transitioning human rights defenders and activists to adopting more comprehensive and technical digital security practices successfully and at scale. Some of this is because the tools remain difficult to use, can be challenging to assimilate into existing workflows, or barely exist for core practices such as social media use. Likewise, some difficulties are down to cognitive and linguistic barriers, are indicative of a lack of support within institutions and networks, or a lack of trusted technical support available in local environments.

Several of the findings that emerged from the trainer focused research could arguably be applied to any number of similar capacity building efforts, regardless of the content being taught. This included an affirmation of the network enabling affects of face-to-face training and the overwhelming success of trainers who hold an equal skill-base in adult learning and facilitation skills, and in the technicalities of the topic being taught. This also included recognisable challenges and difficulties in training, including the significance of effective participant selection, false expectations, inadequate design of interventions on the part of organisers and funders, and the need for greater resources to enable co-training, follow-up training, mentoring and longer-term views on evaluation.

While the specific details of how these challenges manifest themselves in digital security capacity building endeavours are unique, or may at times be more acute, the broader reflections from this part of the research should be of interest to anyone designing capacity building initiatives within such communities. More specifically, the research shows that in the case of digital security capacity building, the sector is only now beginning to mature and there is a need to more adequately clarify frameworks, methodologies, processes and expectations. This will inform what can be expected from an effective training and a good trainer, and how best to design such interventions for longer term and larger scale impact. Moreover, it reaffirms the need for investing in the training community itself, its development, the sharing of skills and resources, and in peer-training and exchange. This is an expensive and energy intensive endeavour, however our research supports the idea that reducing support for this results in a false economy when it comes to the impact and on-going effectiveness of training practices overall.

This image and the others used on this site were created as part of a training exercise during the Security in Context study. Participants, who were human rights defenders and advocates, were asked to draw how they perceived the internet.

Shared Findings

The most overwhelming and common finding across both studies was that digital security has to be taught within communities and within existing networks and collaborative structures. In our view, the research showed that digital security taught in a one-off encounter, or on an individual basis rarely works. Community or collective learning is an essential element on multiple levels. First and most simply, it enables many of the tools and techniques being taught to be put into practice - by their very nature many of the technologies are network or communications based (i.e. requiring two or more users). Second, it allows for contextual and community specific recognition of threats and identification of priorities, enabling the collaborative development of essential mitigation and control strategies. Third, it allows for in-community peer-support and reinforcement of learning. Simply put, after a training, a participant can ask a colleague or trusted partner to show them again, remind them how to do something, or troubleshoot a problem together, creating the directly relevant and viable support network necessary for moving from theory to practice.

Both of the research and learning studies identified this collective and community effort as a key ingredient to success and as a required element in addressing current failures in the long-term effectiveness of digital security trainings. As the digital security expert Bruce Schneier states, “security is a team sport”. What also surfaced in both studies was the importance of follow-up trainings, mentoring and recognition of the inevitable role many participants take after a training in sharing their skills with others. This was seen as essential to enabling the spread of knowledge, yet also a path to be taken with caution - being wary of irresponsible training design where unrealistic expectations are placed on participants to share their skills after a training - both in terms of participants having the time and the depth of knowledge to do so. This points not to an effort to turn all training participants into future trainers, but rather to begin to recognise a sub-set of former participants who have the potential to become advocates and peer-educators in their communities.

Looking Ahead

Recognising that the design of trainings and learning based interventions needs to be improved to meet the changing contexts of human rights defenders, as well as the shifting technological landscapes in which they work, a new approach needs to be developed, that acknowledges and supports the development and growth of in-community awareness raising and peer-support mechanisms; one that recognises digital security as an on-going, expanding and long-term challenge in NGO and activist communities and therefore invests in multi-year funded efforts at scale. This means working to develop and support in-community awareness and collective learning, while simultaneously ensuring complimentary, targeted, intensive and in-depth training for those who face particularly high risk within these communities. These learnings have contributed to the following re-visioning of Tactical Tech's work:

- In terms of skills-building, two broad needs have been identified: to offer a more detailed, pedagogically robust curriculum for those who are particularly vulnerable or are living and working in high risk contexts; and, in parallel, to raise awareness around 'digital privacy consciousness' related to managing social media profiles and data privacy. The latter affects a broad range of our audience, including human rights defenders, some of whom rely considerably on these platforms for their work. As the case studies indicate, some of these skills can be more easily and quickly learned. At one level this is an artificial separation, particularly in terms of those who are working on projects that are high risk; the separation is being made here to facilitate training intervention design.

- Training in digital security and privacy can take a more 'action-based' approach and focus on giving human rights defenders custom support in different time-based contexts: to secure communities and networks; to enable secure workflows; and to support short events and actions to be more secure. Thus, training interventions become more long term investments to support communities, can be task oriented to support workflows and timed and focused on temporarily connected groups to support events and actions to be secure.

- Drawing from the two points above, there is a need to shift how we think about training in terms of a methodological approach to technology capacity building for human rights defenders. For Tactical Tech this means developing an approach that integrates the contextual realities of human rights defenders with their strategic focus, the techniques needed to do their work, and the tools that enable these techniques. For example, investigation is a technique that requires a range of tools, and helps to achieve a strategic vision. A methodological approach that integrates all three contextually would be required to support human rights defenders engaged in investigations.

It is our hope that in sharing the details of this research more broadly, we can contribute to learning and reflection within the sector. Further, we hope that the findings shared will help inform future research efforts and initiatives, encouraging others to conduct research building and expanding on the topics covered here.

Stephanie Hankey, Tactical Tech

Download All

Download All